Publications

Brainstem regulation of slow-wave-sleep

Recent work has helped reconcile puzzling results from brainstem transection studies first performed over 60 years ago, which suggested the existence of a sleep-promoting system in the medullary brainstem. It was specifically shown that GABAergic neurons located in the medullary brainstem parafacial zone (PZGABA) are not only necessary for normal slow-wave-sleep (SWS) but that their selective activation is sufficient to induce SWS in behaving animals. In this review we discuss early experimental findings that inspired the hypothesis that the caudal brainstem contained SWS-promoting circuitry. We then describe the discovery of the SWS-promoting PZGABA and discuss future experimental priorities.

Ventral medullary control of rapid eye movement sleep and atonia

Discrete populations of neurons at multiple levels of the brainstem control rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and the accompanying loss of postural muscle tone, or atonia. The specific contributions of these brainstem cell populations to REM sleep control remains incompletely understood. Here we show in rats that viral vector-based lesions of the ventromedial medulla at a level rostral to the inferior olive (pSOM) produced violent myoclonic twitches and abnormal electromyographic spikes, but not complete loss of tonic atonia, during REM sleep. Motor tone during non-REM (NREM) sleep was unaffected in these same animals. Acute chemogenetic activation of pSOM neurons in rats robustly and selectively suppressed REM sleep but not NREM sleep. Similar lesions targeting the more rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) did not affect sleep or atonia, while chemogenetic stimulation of the RVM produced wakefulness and reduced sleep. Finally, selective activation of vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) pSOM neurons in mice produced complete suppression of REM sleep whereas their loss increased EMG spikes during REM sleep. These results reveal a key contribution of the pSOM and specifically the VGAT+ neurons in this region in REM sleep and motor control.

Cholinergic, Glutamatergic, and GABAergic Neurons of the Pedunculopontine Tegmental Nucleus Have Distinct Effects on Sleep/Wake Behavior in Mice

The pedunculopontine tegmental (PPT) nucleus has long been implicated in the regulation of cortical activity and behavioral states, including rapid eye-movement (REM) sleep. For example, electrical stimulation of the PPT region during sleep leads to rapid awakening, whereas lesions of the PPT in cats reduce REM sleep. Though these effects have been linked with the activity of cholinergic PPT neurons, the PPT also includes intermingled glutamatergic and GABAergic cell populations, and the precise roles of cholinergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic PPT cell groups in regulating cortical activity and behavioral state remain unknown. Using a chemogenetic approach in three Cre-driver mouse lines, we found that selective activation of glutamatergic PPT neurons induced prolonged cortical activation and behavioral wakefulness, whereas inhibition reduced wakefulness and increased non-REM (NREM) sleep. Activation of cholinergic PPT neurons suppressed lower-frequency electroencephalogram rhythms during NREM sleep. Last, activation of GABAergic PPT neurons slightly reduced REM sleep. These findings reveal that glutamatergic, cholinergic, and GABAergic PPT neurons differentially influence cortical activity and sleep/wake states.

A Novel Population of Wake-Promoting GABAergic Neurons in the Ventral Lateral Hypothalamus

The largest synaptic input to the sleep-promoting ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) arises from the lateral hypothalamus, a brain area associated with arousal. However, the neurochemical identity of the majority of these VLPO-projecting neurons within the lateral hypothalamus (LH), as well as their function in the arousal network, remains unknown. Herein we describe a population of VLPO-projecting neurons in the LH that express the vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT; a marker for GABA-releasing neurons). In addition to the VLPO, these neurons also project to several other established sleep and arousal nodes, including the tuberomammillary nucleus, ventral periaqueductal gray, and locus coeruleus. Selective and acute chemogenetic activation of LH VGAT+ neurons was profoundly wake promoting, whereas acute inhibition increased sleep. Because of its direct and massive inputs to the VLPO, this population may play a particularly important role in sleep-wake switching.

How genetically engineered systems are helping to define, and in some cases redefine, the neurobiological basis of sleep and wake

The advent of genetically engineered systems, including transgenic animals and recombinant viral vectors, has facilitated a more detailed understanding of the molecular and cellular substrates regulating brain function. In this review we highlight some of the most recent molecular biology and genetic technologies in the experimental “systems neurosciences,” many of which are rapidly becoming a methodological standard, and focus in particular on those tools and techniques that permit the reversible and cell-type specific manipulation of neurons in behaving animals. These newer techniques encompass a wide range of approaches including conditional deletion of genes based on Cre/loxP technology, gene silencing using RNA interference, cell-type specific mapping or ablation and reversible manipulation (silencing and activation) of neurons in vivo. Combining these approaches with viral vector delivery systems, in particular adeno-associated viruses (AAV), has extended, in some instances greatly, the utility of these tools. For example, the spatially- and/or temporally-restricted transduction of specific neuronal cell populations is now routinely achieved using the combination of Cre-driver mice and stereotaxic-based delivery of AAV expressing Cre-dependent cassettes. We predict that the experimental application of these tools, including creative combinatorial approaches and the development of even newer reagents, will prove necessary for a complete understanding of the neuronal circuits subserving most neurobiological functions, including the regulation of sleep and wake.

The anatomical, cellular and synaptic basis of motor atonia during rapid eye movement sleep

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is a recurring part of the sleep–wake cycle characterized by fast, desynchronized rhythms in the electroencephalogram (EEG), hippocampal theta activity, rapid eye movements, autonomic activation and loss of postural muscle tone (atonia). The brain circuitry governing REM sleep is located in the pontine and medullary brainstem and includes ascending and descending projections that regulate the EEG and motor components of REM sleep. The descending signal for postural muscle atonia during REM sleep is thought to originate from glutamatergic neurons of the sublaterodorsal nucleus (SLD), which in turn activate glycinergic pre‐motor neurons in the spinal cord and/or ventromedial medulla to inhibit motor neurons. Despite work over the past two decades on many neurotransmitter systems that regulate the SLD, gaps remain in our knowledge of the synaptic basis by which SLD REM neurons are regulated and in turn produce REM sleep atonia. Elucidating the anatomical, cellular and synaptic basis of REM sleep atonia control is a critical step for treating many sleep‐related disorders including obstructive sleep apnoea (apnea), REM sleep behaviour disorder (RBD) and narcolepsy with cataplexy.

Neuroscience: A Distributed Neural Network Controls REM Sleep

How does the brain control dreams? New science shows that a small node of cells in the medulla — the most primitive part of the brain — may function to control REM sleep, the brain state that underlies dreaming.

Basal forebrain control of wakefulness and cortical rhythms

Wakefulness, along with fast cortical rhythms and associated cognition, depend on the basal forebrain (BF). BF cholinergic cell loss in dementia and the sedative effect of anti-cholinergic drugs have long implicated these neurons as important for cognition and wakefulness. The BF also contains intermingled inhibitory GABAergic and excitatory glutamatergic cell groups whose exact neurobiological roles are unclear. Here we show that genetically targeted chemogenetic activation of BF cholinergic or glutamatergic neurons in behaving mice produced significant effects on state consolidation and/or the electroencephalogram but had no effect on total wake. Similar activation of BF GABAergic neurons produced sustained wakefulness and high-frequency cortical rhythms, whereas chemogenetic inhibition increased sleep. Our findings reveal a major contribution of BF GABAergic neurons to wakefulness and the fast cortical rhythms associated with cognition. These findings may be clinically applicable to manipulations aimed at increasing forebrain activation in dementia and the minimally conscious state.

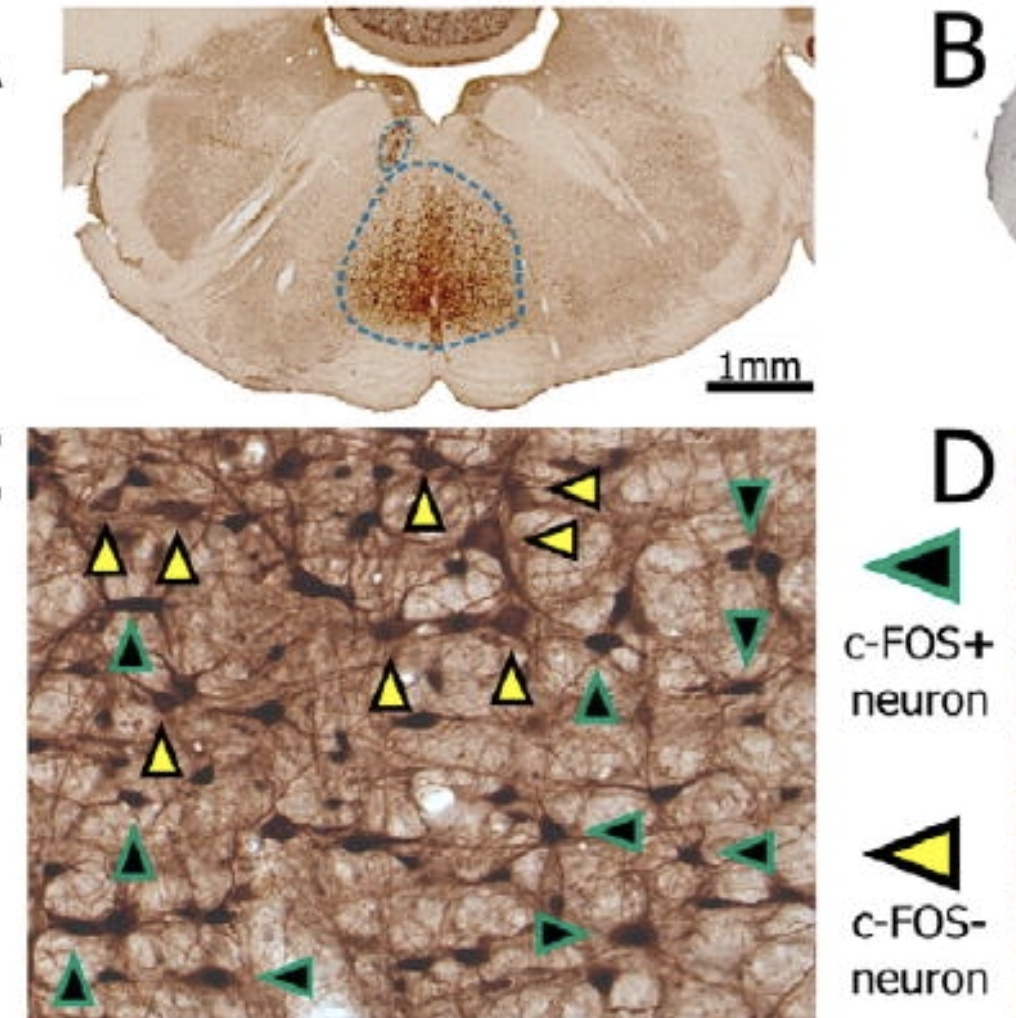

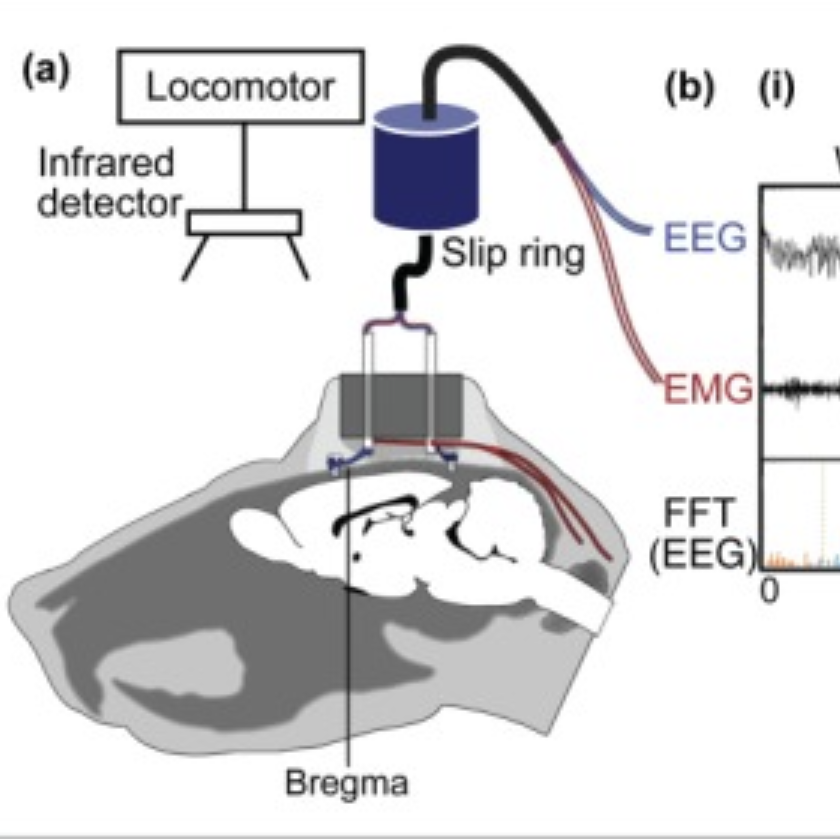

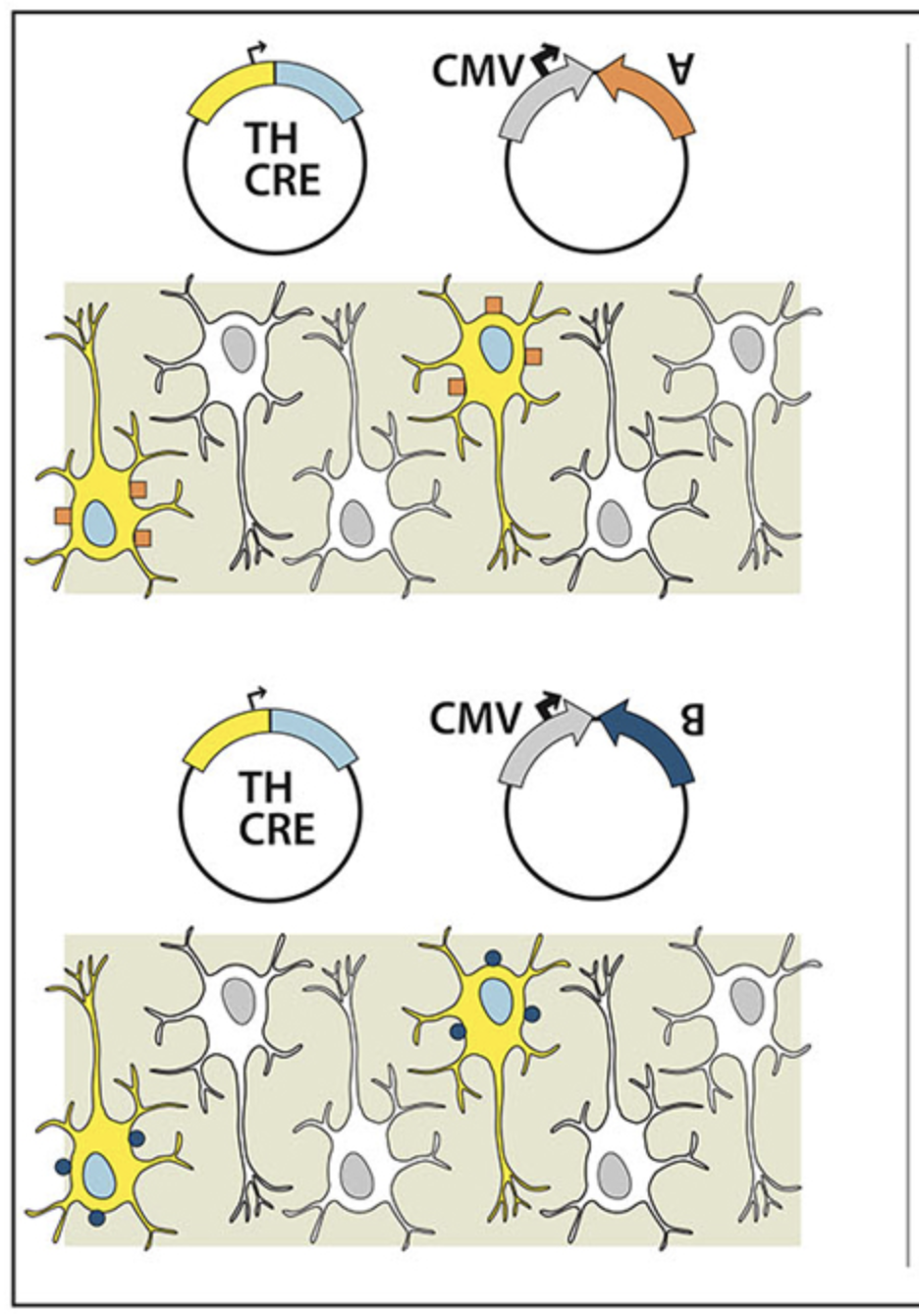

Targeted genetic manipulations of neuronal subtypes using promoter-specific combinatorial AAVs in wild-type animals

Techniques to genetically manipulate the activity of defined neuronal subpopulations have been useful in elucidating function, however applicability to translational research beyond transgenic mice is limited. Subtype targeted transgene expression can be achieved using specific promoters, but often currently available promoters are either too large to package into many vectors, in particular adeno-associated virus (AAV), or do not drive expression at levels sufficient to alter behavior. To permit neuron subtype specific gene expression in wildtype animals, we developed a combinatorial AAV targeting system that drives, in combination, subtype specific Cre-recombinase expression with a strong but non-specific Cre-conditional transgene. Using this system we demonstrate that the tyrosine hydroxylase promoter (TH-Cre-AAV) restricted expression of channelrhodopsin-2 (EF1α-DIO-ChR2-EYFP-AAV) to the rat ventral tegmental area (VTA), or an activating DREADD (hSyn-DIO-hM3Dq-mCherry-AAV) to the rat locus coeruleus (LC). High expression levels were achieved in both regions. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed the majority of ChR2+ neurons (>93%) colocalized with TH in the VTA, and optical stimulation evoked striatal dopamine release. Activation of TH neurons in the LC produced sustained EEG and behavioral arousal. TH-specific hM3Dq expression in the LC was further compared with: (1) a Cre construct driven by a strong but non-specific promoter (non-targeting); and (2) a retrogradely-transported WGA-Cre delivery mechanism (targeting a specific projection). IHC revealed that the area of c-fos activation after CNO treatment in the LC and peri-LC neurons appeared proportional to the resulting increase in wakefulness (non-targeted > targeted > ACC to LC projection restricted). Our dual AAV targeting system effectively overcomes the large size and weak activity barrier prevalent with many subtype specific promoters by functionally separating subtype specificity from promoter strength.

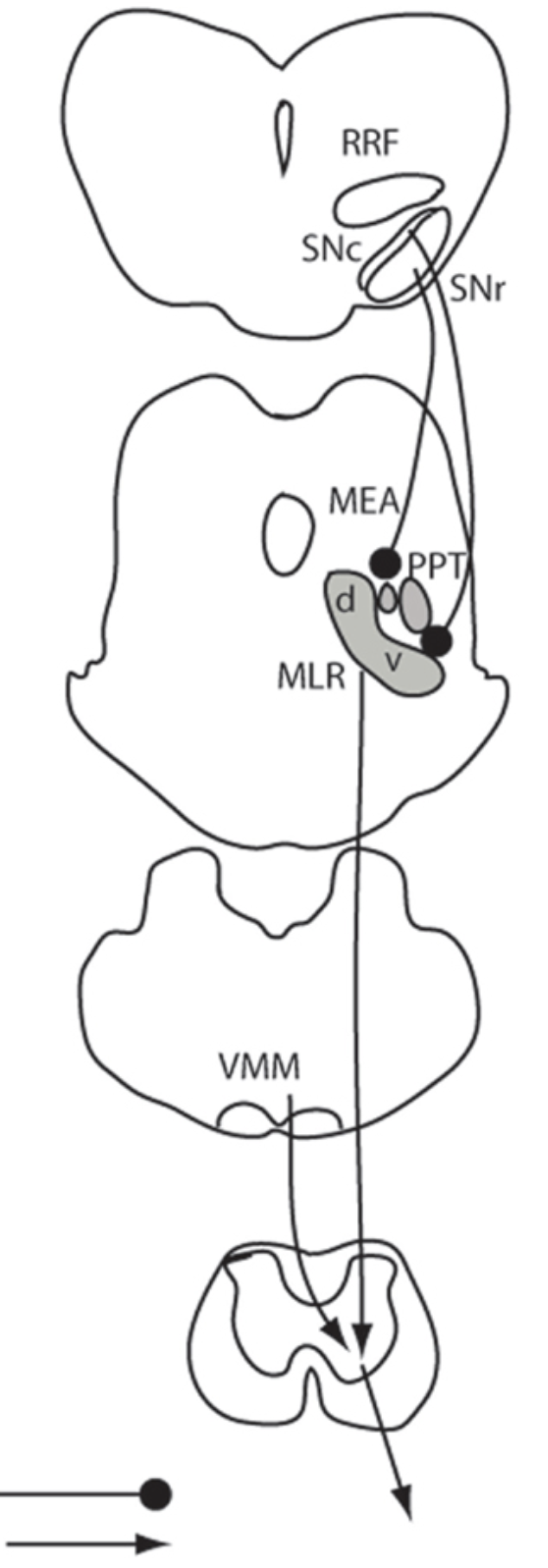

Anatomical location of the mesencephalic locomotor region and its possible role in locomotion, posture, cataplexy, and Parkinsonism

The mesencephalic (or midbrain) locomotor region (MLR) was first described in 1966 by Shik and colleagues, who demonstrated that electrical stimulation of this region induced locomotion in decerebrate (intercollicular transection) cats. The pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus (PPT) cholinergic neurons and midbrain extrapyramidal area (MEA) have been suggested to form the neuroanatomical basis for the MLR, but direct evidence for the role of these structures in locomotor behavior has been lacking. Here, we tested the hypothesis that the MLR is composed of non-cholinergic spinally projecting cells in the lateral pontine tegmentum. Our results showed that putative MLR neurons medial to the PPT and MEA in rats were non-cholinergic, glutamatergic, and express the orexin (hypocretin) type 2 receptors. Fos mapping correlated with motor behaviors revealed that the dorsal and ventral MLR are activated, respectively, in association with locomotion and an erect posture. Consistent with these findings, chemical stimulation of the dorsal MLR produced locomotion, whereas stimulation of the ventral MLR caused standing. Lesions of the MLR (dorsal and ventral regions together) resulted in cataplexy and episodic immobility of gait. Finally, trans-neuronal tracing with pseudorabies virus demonstrated disynaptic input to the MLR from the substantia nigra via the MEA. These findings offer a new perspective on the neuroanatomic basis of the MLR, and suggest that MLR dysfunction may contribute to the postural and gait abnormalities in Parkinsonism.

Medial Amygdalar Aromatase Neurons Regulate Aggression in Both Sexes

Aromatase-expressing neuroendocrine neurons in the vertebrate male brain synthesize estradiol from circulating testosterone. This locally produced estradiol controls neural circuits underlying courtship vocalization, mating, aggression, and territory marking in male mice. How aromatase-expressing neuronal populations control these diverse estrogen-dependent male behaviors is poorly understood, and the function, if any, of aromatase-expressing neurons in females is unclear. Using targeted genetic approaches, we show that aromatase-expressing neurons within the male posterodorsal medial amygdala (MeApd) regulate components of aggression, but not other estrogen-dependent male-typical behaviors. Remarkably, aromatase-expressing MeApd neurons in females are specifically required for components of maternal aggression, which we show is distinct from intermale aggression in pattern and execution. Thus, aromatase-expressing MeApd neurons control distinct forms of aggression in the two sexes. Moreover, our findings indicate that complex social behaviors are separable in a modular manner at the level of genetically identified neuronal populations.

Identification of a direct GABAergic pallidocortical pathway in rodents

The basal ganglia, interacting with the cortex, play a critical role in a range of behaviors. Output from the basal ganglia to the cortex is thought to relay through the thalamus, yet an intriguing alternative is that the basal ganglia may directly project to, and communicate with, the cortex. We explored an efferent projection from the globus pallidus externa (GPe), a key hub in the basal ganglia system, to the cortex of rats and mice. Anterograde and retrograde tracing revealed projections to the frontal premotor cortex, especially the deep projecting layers, originating from GPe neurons that receive axonal inputs from the dorsal striatum. Cre-dependent anterograde tracing in GPe Vgat-ires-cre mice confirmed that the pallidocortical projection is GABAergic, and in vitro optogenetic stimulation in the cortex of these projections produced a fast inhibitory postsynaptic current in targeted cells that was abolished by bicucculine. The pallidocortical projections targeted GABAergic interneurons and, to a lesser extent, pyramidal neurons. This GABAergic pallidocortical pathway directly links the basal ganglia and cortex and may play a key role in behavior and cognition in normal and disease states.

Impaired circadian photosensitivity in mice lacking glutamate transmission from retinal melanopsin cells

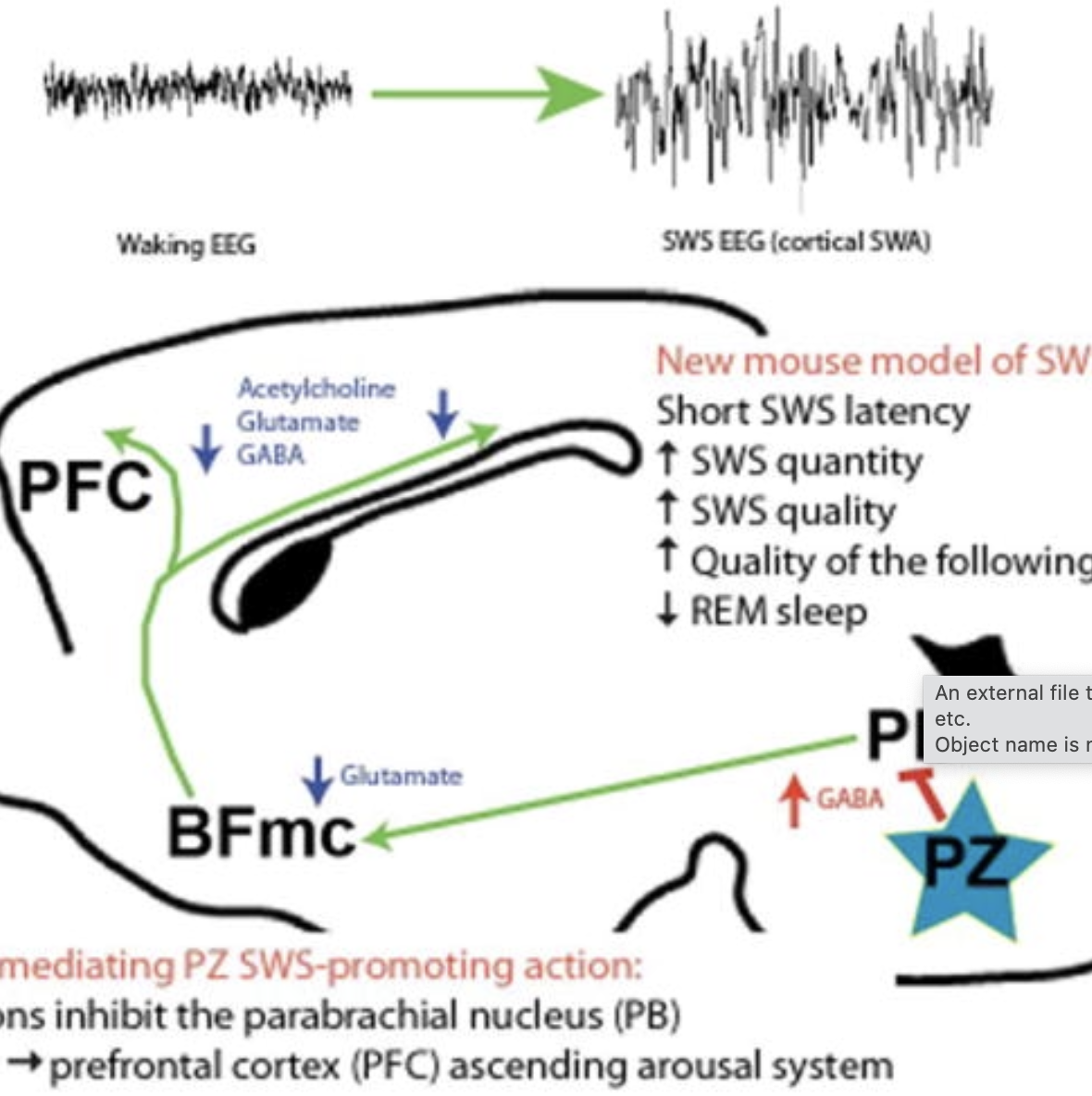

Work in animals and humans has suggested the existence of a slow wave sleep (SWS)-promoting/electroencephalogram (EEG)-synchronizing center in the mammalian lower brainstem. Although sleep-active GABAergic neurons in the medullary parafacial zone (PZ) are needed for normal SWS, it remains unclear whether these neurons can initiate and maintain SWS or EEG slow-wave activity (SWA) in behaving mice. We used genetically targeted activation and optogenetically based mapping to examine the downstream circuitry engaged by SWS-promoting PZ neurons, and we found that this circuit uniquely and potently initiated SWS and EEG SWA, regardless of the time of day. PZ neurons monosynaptically innervated and released synaptic GABA onto parabrachial neurons, which in turn projected to and released synaptic glutamate onto cortically projecting neurons of the magnocellular basal forebrain; thus, there is a circuit substrate through which GABAergic PZ neurons can potently trigger SWS and modulate the cortical EEG.n idea.

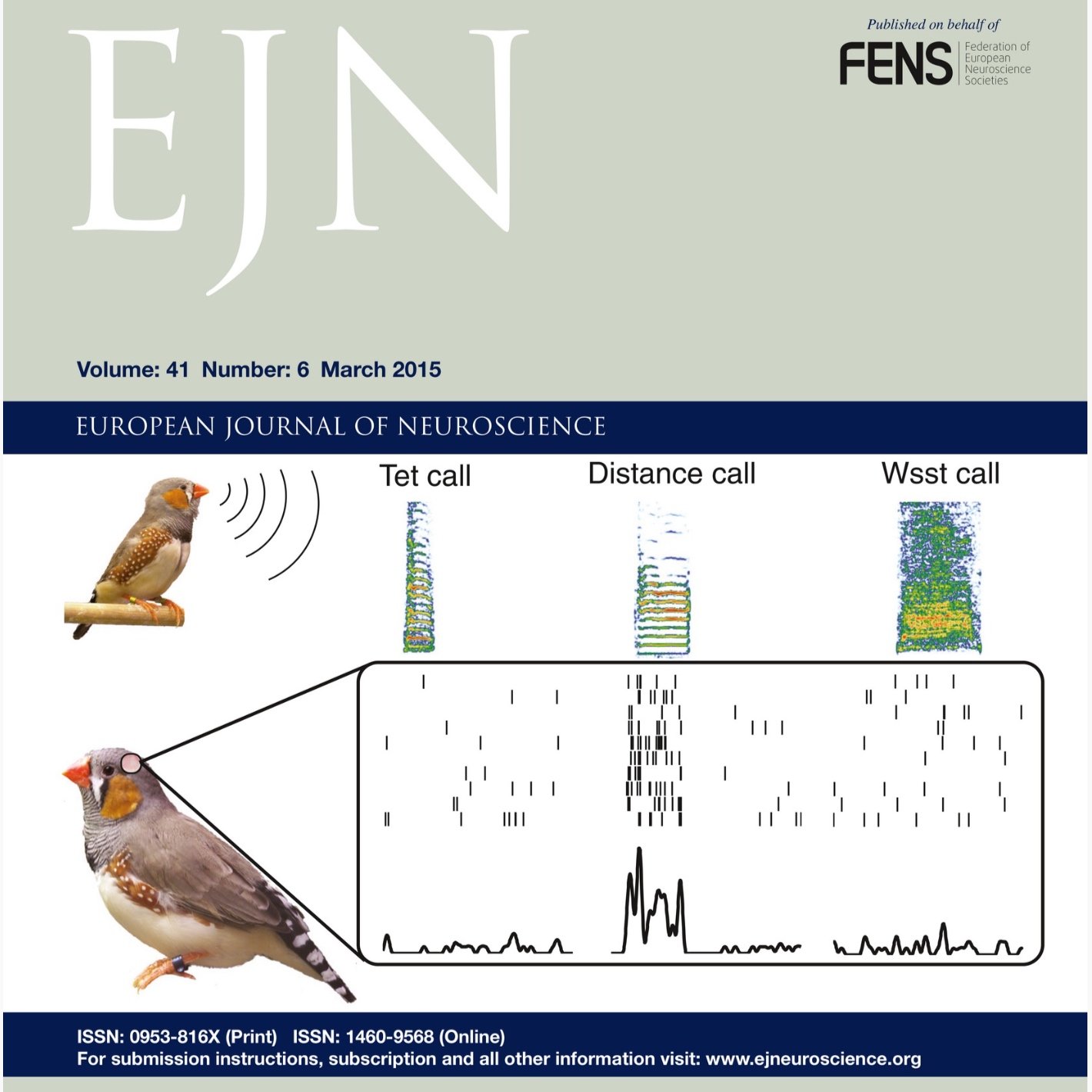

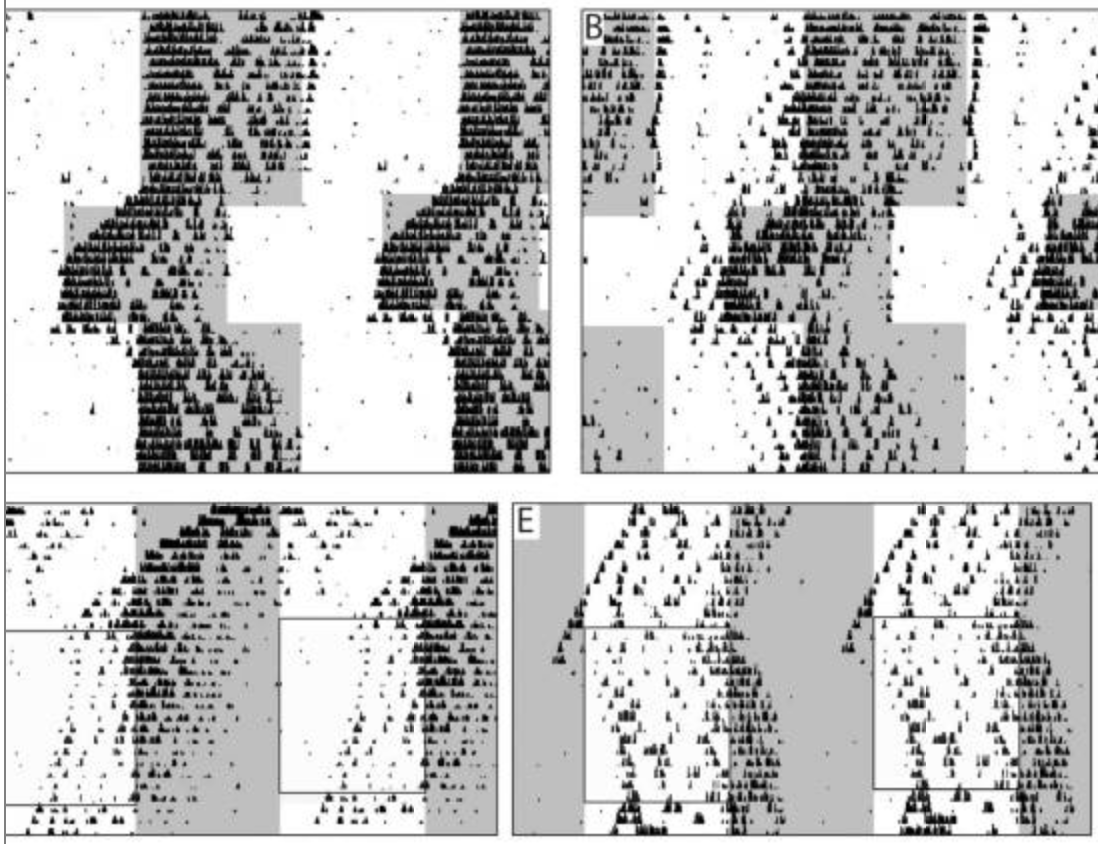

Acute inhibition of a cortical motor area impairs vocal control in singing zebra finches

Genetically targeted approaches that permit acute and reversible manipulation of neuronal circuit activity have enabled an unprecedented understanding of how discrete neuronal circuits control animal behavior. Zebra finch singing behavior has emerged as an excellent model for studying neuronal circuit mechanisms underlying the generation and learning of behavioral motor sequences. We employed a newly developed, reversible, neuronal silencing system in zebra finches to test the hypothesis that ensembles of neurons in the robust nucleus of the arcopallium (RA) control the acoustic structure of specific song parts, but not the timing nor the order of song elements. Subunits of an ivermectin-gated chloride channel were expressed in a subset of RA neurons, and ligand administration consistently suppressed neuronal excitability. Suppression of activity in a group of RA neurons caused the birds to sing songs with degraded elements, although the order of song elements was unaffected. Furthermore some syllables disappeared in the middle or at the end of song motifs. Thus, our data suggest that generation of specific song parts is controlled by a subset of RA neurons, whereas elements order coordination and timing of whole songs are controlled by a higher premotor area.

MC4R-expressing glutamatergic neurons in the paraventricular hypothalamus regulate feeding and are synaptically connected to the parabrachial nucleus

Both in rodents and humans, melanocortin-4 receptors (MC4Rs) suppress appetite and prevent obesity. Unfortunately, the underlying neural mechanisms by which MC4Rs regulate food intake are poorly understood. Unraveling these mechanisms may open up avenues for treating obesity. In the present study we have established that MC4Rs on neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus are both necessary and sufficient for MC4R control of feeding and that these neurons are glutamatergic and not GABAergic and do not express the neuropeptides oxytocin, corticotropin-releasing hormone, prodynorphin, or vasopressin. In addition, we identify downstream projections from these glutamatergic neurons to the lateral parabrachial nucleus, which could mediate the appetite suppressing effects.

GABAergic parafacial zone is a medullary slow–wave–sleep promoting center

Work in animals and humans suggest the existence of a slow–wave sleep (SWS) promoting/EEG synchronizing center in the mammalian lower brainstem. While sleep–active GABAergic neurons in the medullary parafacial zone (PZ) are needed for normal SWS, it remains unclear if these neurons can initiate and maintain SWS or EEG slow wave activity (SWA) in behaving mice. We used genetically targeted activation and optogenetic–based mapping to uncover the downstream circuitry engaged by SWS–promoting PZ neurons, and we show that this circuit uniquely and potently initiates SWS and EEG SWA, regardless of the time of day. PZ neurons monosynaptically innervate and release synaptic GABA onto parabrachial neurons that in turn project to and release synaptic glutamate onto cortically–projecting neurons of the magnocellular basal forebrain; hence a circuit substrate is in place through which GABAergic PZ neurons can potently trigger SWS and modulate the cortical EEG.